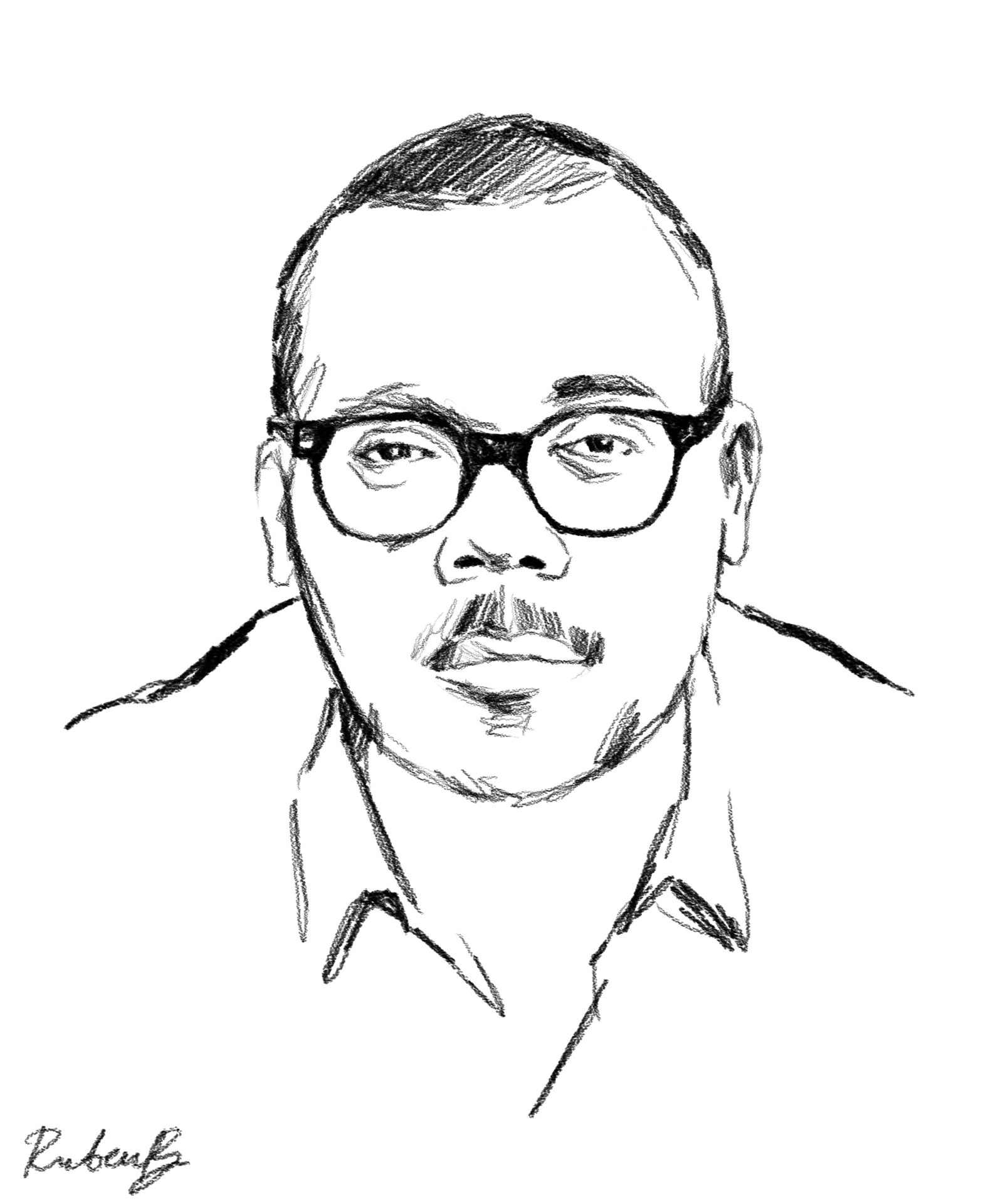

ASK A SANE PERSON

Chris Jackson on Why the Status Quo is Killing Us

The books that are published, and the authors who get their stories told, have a maximum impact on the culture at large, and the circulation of these books quite literally saves lives, rewrites policy, and changes the world. Perhaps no publisher has done more in recent years to retune our social brainwaves—particularly on the subject of race—than the editor-in-chief of One World (an imprint of Random House). Chris Jackson is already a literary legend—working as the editor and publisher for superstars such as Ta-Nehisi Coates and Jay-Z. But Jackson’s mission continues and expands as he continues to publish an astonishing array of writers across genres and backgrounds. Part of why bookstores still feel like vital forums has to do with Jackson’s daring work. So we checked in to find out where he felt like we, as a people, are headed.

———

INTERVIEW: Where are you and how long have you been isolating?

CHRIS JACKSON: I’ve stuck it out in Brooklyn and I’ve been isolating as long as everyone else in this city, i.e., several years now. My isolation partner has been my son, at least half the time—he’s 12 and great company, I really couldn’t ask for better, but he probably could. The summer was surreal for us as for everyone; I’d peel myself off the floor from a day of frantic work and we’d spend the warm nights sitting on a blanket in the grass or perched on the rocks where we’d watch the sun set over the Manhattan skyline across the river—a whole abandoned civilization of empty office buildings, god, they looked so solemn but also demented, confused—and helicopters menacing protestors on the bridges, and fireworks exploding in every direction, and the geese and rats and birds claiming the empty park. The echo of ambulances still in our ears from the horrific spring. I’m a lifelong New Yorker, and felt like I was watching the city trying to make sense of itself, find a way to grieve and protest and survive, but also renew itself, find some kind of purpose and function. While having a breakdown. Helicopters, explosions, chants, banging pots, and ovations, sirens! And still so much silence.

INTERVIEW: What has this pandemic confirmed or altered about your view of society?

JACKSON: It’s confirmed that this country’s racism and hatred of the poor knows no bounds—that we might prefer to kill ourselves before we take care of each other. We organized a series of virtual events at the start of the pandemic—Ideas x Action—with our authors. One of the first was with Ta-Nehisi Coates and Heather McGhee, early in the pandemic, and we wondered aloud whether this pandemic would finally be the thing that shows us that we’re all really connected, that if one is sick, if one is oppressed, if one is broken and impoverished, it affects us all. A mysterious virus seems like a perfect metaphor for connection—for the necessity of taking care of each other, because if any one of us is ill, we’re all at risk. But it turns out the virus wasn’t enough to bring us together—the devastation fell so hard on Black and Brown and poor people, while the hyper-wealthy thrived. What a damning and revealing outcome! It was unsurprising but still maddening and heartbreaking to watch it unfold as it did.

INTERVIEW: What is the worst-case scenario for the future?

JACKSON: We revert to the status quo ante, which is to say, we revert to the same society that got us into this mess, the one that, when confronted with a crisis, found itself without resources or leadership or solidarity, only chaos and scams and acrimony and fatal incompetence.

INTERVIEW: What good can come out of this lockdown? Are there any reasons to hope?

JACKSON: It’s made the need for radical change more evident, of course. Going back to those office buildings—when I looked at them, it reminded me that no matter how deeply invested we are in certain ideas and customs, we are capable of sudden change and adaptation. We built our white-collar world around offices—our cities, our transportation, our wardrobes, our days—but then stopped overnight. And the world didn’t crumble. I’ve gone into an office practically every weekday since I turned 18! But now it is the office that seems strange, not its absence. Radical change is possible, no matter how people try to scare us into thinking the status quo is all that keeps us from disaster. We abolished the office, literally overnight, and, with hope, it will never be the same. What else can we abolish? What else can we remake? What other dehumanizing or broken or just badly designed systems can we re-engineer for human happiness and safety and thriving? Our imaginations, I hope, are freer now to tackle these exciting questions. The status quo is killing us.

INTERVIEW: What has been your daily routine during this time?

JACKSON: It’s varied. Mostly these weekdays I wake up, take a winding walk by the river to my local coffee hole-in-the-wall; buy myself a latte and my son a hot chocolate. Wake him up with the hot chocolate. Drink my latte and make breakfast—sometimes we read a passage from Ross Gay’s Book of Delights to start the day, to keep our antennae up for random delightful things. Then he takes over the living room for school, I work at my desk in my bedroom. We take a bike ride or walk in the evening and eat dinner (half the time we cook; half we order out or pick something up on our walk), then we both do our homework—mine is editing. Sometimes we watch a show together—we recently finished up Cobra Kai, a fantasy world where kids actually touch each other, even if the touches are karate kicks to the face—sometimes he plays video games with his friends; sometimes we do a YouTube workout together (I love the six-minute workouts and will probably never go to a gym again); sometimes we work on other projects (he debates and plays guitar and has sports; I try to keep the dishwasher empty). Eventually he heads to bed and then I FaceTime friends to talk or bake together or meet someone on the roof or in the park for a drink or I just collapse in surprised exhaustion. On the days he’s with his mother, the routine is similar, if sometimes more adult-oriented.

INTERVIEW: Describe the current state of your hair?

JACKSON: My hair got relatively long and bushy during the first several months of the pandemic, which was fun until it wasn’t—and then I gave it one good self-cut and then one terrible one, which was fine because who cared? I wore a hat. Okay, I cared, even under the hat, I could feel the bad haircut. It changes you, a bad haircut, seeps into your brain. So as soon as barbershops reopened, I had a tearful reunion with my barber Speedy at Astor Place, who has been cutting my hair for a decade or more. Its current state is as good as it gets, which is meh.

INTERVIEW: On a scale of 1 to 10, what is your level of panic about the current state of the world?

JACKSON: I am naturally somewhat depressive and a little paranoid, so either I don’t panic or I’m always sort of panicked but with the calm of someone who knows the panic is never going to stop so why stress about it? We live in an entropic universe. I’ll say 5. Or 10.

INTERVIEW: Do you think there is hope for true racial equality in the United States? What do you think is the first step in that goal?

JACKSON: I think there’s hope, of course, and the first step is a pretty obvious one: some kind of truth and reconciliation process that allows us to establish a common story, a common understanding, a common history around exactly how racism has worked in our country, how it has benefited some and destroyed others and taken a toll on practically all of us. A lot of the publishing we do is trying to find ways of setting down that story—in some cases, like in the 1619 Project books we’re working on, it’s about talking about the legacies of slavery in our current systems. In others, as in the work of Bryan Stevenson, it’s about memorializing the dead, grieving together over the atrocities we’ve committed. Some, like Ta-Nehisi Coates, and his essay “The Case for Reparations” in particular, are about delineating the actual process and price of white supremacist policy. Or Ibram X. Kendi, who shows how intensely damaging racist ideas follow those policies. Or a book we just announced that we’re publishing with Eve Ewing about how our education system was engineered to make Black and native Americans into second-class citizens. Or Heather McGhee’s upcoming book, which lays out how truth and reconciliation might look in practice. I think this understanding is crucial because it tells us not only how white supremacy has worked in this country, but how deeply it has infected our systems and at what cost—so we can understand that to solve the problem, we have to go into those systems, into those policies, and re-engineer them toward equity and justice. It’s not just a spiritual and emotional exercise—although it is those things, too. It’s a first step on a long, long road.

INTERVIEW: Do you think protests are effective tools for changing the system? How does it make a difference in the long term?

JACKSON: Protests are essential, but they have to work hand-in-hand with other forms of pressure and persuasion, including electoral politics and cultural change. I think there’s a consensus that protestors should also vote; but, as Ta-Nehisi and others have said, it’s also essential that voters protest. We just published a book with Alicia Garza, one of the “founders” of BLM and a hero of mine. Her argument is that protest is also a way of connecting people, which is at the heart of all activism and organization in her mind: connection. We see each other out there and are strengthened. Marching down Fifth Avenue one day this summer in a mixed-race, mixed-age crowd of masked protestors, chanting the names of the dead, I also felt the prefigurative aspect of protest, an idea that was introduced to me by the late David Graeber when I worked with him on his book about the Occupy movement—that we see in the protest the world we want to create.

INTERVIEW: How do you personally channel your anger? Do you find anger to be a useful emotion?

JACKSON: I don’t get angry, generally, but I think it’s because that part of me died at some point in my life. I grew up in a place where expressing anger could easily get you killed. But Valarie Kaur, one of our authors, has an idea in her book See No Stranger that I find very compelling—that rage is an essential part of love; the rage to protect the innocent, rage that drives us to fight for justice, but also rage to express rightful anger when we’ve been abused or treated unjustly—to make sure that we don’t internalize that anger. We have to find safe ways to practice it, but as Toni Morrison says, it’s so important that we feel what we feel.

INTERVIEW: Which young leaders of the moment inspire you?

JACKSON: I’m inspired by young writers and people in the literary world who are trying to change the way we tell stories—people who are not trying to curry the favor of gatekeepers the way young people of my generation, I think, really struggled with. In my own industry, that means people like Danny Vasquez who’ve organized walkouts and other protests against book publishers. Playwrights like Jeremy O. Harris and Jackie Sibblies Drury who are interrogating the idea of the white gaze very directly. At One World, we published Karla Cornejo Villavicencio’s book The Undocumented Americans this year—it’s a finalist for the National Book Award—and she’s heroic to me, someone who puts herself on the line in very real ways to tell the stories she needs to tell the way she needs to tell them, with no special regard for traditional form or readers who want to be coddled. We’re publishing a book this fall with Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham called Black Futures that is full of beautiful, radical art by mostly young Black creators—some in traditional forms like painting or essay, but some in the form of IG posts, tweets, street art, and communal gatherings—who understand that the culture needs to be challenged at every turn and radically reborn along principles of honesty, inclusion, and justice, but also love and connection and joy.

INTERVIEW: What’s the next step after protests in the streets? Where does the righteous rage go?

JACKSON: We have to remake every one of our systems, and that goes for book publishing as much as anything. We can all throw down our buckets where we are—to misuse a Booker T. Washington-ism—and look at what’s going on right in front of us, and then raise hell: in our industries, our own work, our communities.

INTERVIEW: What thinker have you taken comfort in of late and why?

JACKSON: I’m not sure he counts as a thinker, but I have been thinking a lot about the philosophy of Marlo from The Wire, really as captured in one scene. He’s the rising player in the drug game in Baltimore and everyone knows it. He walks into a bodega and shoplifts some candy right in front of the security guard (why does this bodega have a security guard?). The guard follows him out of the store and protests. He tells Marlo that he’s a man, too, and he can’t just let him so blatantly steal and not say anything. And Marlo sucks on his blowpop, twirls it around a little in his mouth, and then gets in the security guard’s face and repeats several times: “You want it to be one way. But it’s the other way.” This describes so much of the last four years for me. I’m the security guard. Reality is Marlo. I want it to be one way. But it’s the other way. I’ve also been spending some time with adrienne maree brown’s work—she’s one of the thinkers helping me move on from a grim Marlo view of the world, which comes more naturally to me, to one of possibilities and pleasure and new ways of approaching conflict and change.

JACKSON: “It Is What It Is” by Blood Orange is, according to Spotify, the song I’ve played the most this year—seems right.INTERVIEW: If 2020 were a song, which song would it be?

INTERVIEW: Where did we go wrong? Like, what was the exact moment?

JACKSON: I wish I knew. There’s a moment in one of William Vollman’s very, very, very long books about the first encounters between Europeans and indigenous Americans—I think it was Fathers and Crows—where one extended scene stands in for the general moment when European settlers chose war and domination. There’s a similar idea in Ayi Kwei Armah’s Two Thousand Seasons, a book I loved when I first read it, where he describes an idyllic African Eden before white colonialism and Black betrayal ruined it all. I would love for it to be so simple—a Sliding Doors version of history where, if we had just turned left instead of right, history would have unfolded in a very different way. But I don’t believe that. I think the problem goes deeper. There’s no way to MAGA our way back to a purer past. Whatever good there is for us as a species lies ahead.

INTERVIEW: Which (admittedly totally unqualified) celebrity would you trust with the planet’s future?

JACKSON: Lebron James.

INTERVIEW: If you could stop time at one particular moment in your life, which moment would it be?

JACKSON: In 2008, my son was born and by election day he was just a few months old. My then-wife and I invited the then-unknown blogger Ta-Nehisi Coates and his wife Kenyatta and their young son Samori over to watch the election returns. And we woke up our son, Jasper, sleeping in an Obama ’08 onesie, when they called Florida for Obama. The room was full of disbelief. After eight years of George W. Bush and lies and war and financial collapse and Black people on the roofs of flooded houses in New Orleans, a man named Barack Obama was going to be president. Outside the streets of Brooklyn were erupting in celebration. Samori had his first sip of champagne. I knew even then that Obama was not our savior. But I felt like it was a step finally, finally, in a new direction—that my son would be born into a different world than the Nixon-Reagan-Bush nightmare I was born into. I felt hope for him, for me, for us, for the world. The next 12 years, whew. But that moment was magical.

INTERVIEW: What’s one skill we should all learn while in quarantine?

JACKSON: Listening.

INTERVIEW: What does our future as a nation look like?

JACKSON: It’s pretty opaque—it could go a million different directions. I think the primary shift—along with the intensifying climate crisis—is that this country is no longer going to be majority white. I think there is and will be a battle between three different visions when it comes to race: white people who are dead-set on white supremacy qua white supremacy; white people who are willing to accept other groups of immigrants—Latinx, Asian-American—into a whiteness that is really an anti-Black coalition; and a true pluralistic society, based on ideas of equality that Black people have fought for for the last 400 years. My preference is the latter, but I don’t know how it’s going to go.

INTERVIEW: What prevents you from giving up hope in the human race?

JACKSON: This is a presumptuous question. I’m not sure I haven’t given up hope! But I think most people want the same things and are capable of great generosity, compassion, creativity, and, broadly defined, beauty. So that gives me hope. But I know how much damage a small group of venal, selfish, cruel people can do when they seize power. And they always seem to seize power.

INTERVIEW: Who should be the next president of the United States?

JACKSON: Joe Biden.

INTERVIEW: What will happen if Biden gets elected?

JACKSON: We will have to find ways to pressure him on any number of issues, but probably the first is on protecting democracy, i.e., voting rights and accessibility, expansion of the supreme court, maybe rank-choice voting, abolishing the electoral college, adding new states. That’s a real handful but will be the bedrock of every other change that comes.

INTERVIEW: What will happen if Trump gets re-elected?

JACKSON: It’s hard to imagine. I think most of us feel depleted and exhausted by this man and his incompetent grift of an administration, and it’s hard to think about how to keep up the fight for four more years. But we’d have to. I’m not leaving this country, so I have to figure out how to live in it.