IN CONVERSATION

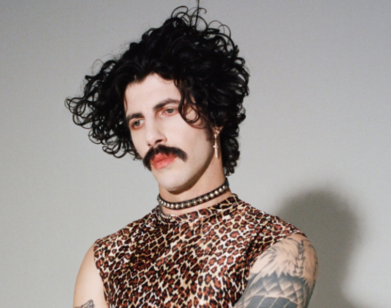

“We’re Doing Zoom Therapy”: Ezra Furman, in Conversation with Sarah Silverman

In All of Us Flames, Ezra Furman pens a record for the apocalypse, but it’s not at all hopeless. This apparent contradiction becomes slightly less mysterious when you consider the circumstances in which the album was made. All of Us Flames was written almost entirely during lockdown, when Furman was raising a young child and beginning to embrace her identity as a trans woman. The result is a powerful meditation on finding community in the face of solitude, with melodies that are at once morose and euphoric, all anchored by Furman’s silvery vocals. Her unique brand of intellectual but deeply-felt art-rock has won her devout fans, including comedy legend Sarah Silverman, who called Furman to chat about Judaism, baby jokes, and the overlap between comedy and music. —CAITLIN LENT

———

SARAH SILVERMAN: Hi Ezra.

EZRA FURMAN: Hi. What’s up? I don’t know what’s going on.

SILVERMAN: Me neither. But all we have to do is have a conversation.

FURMAN: Cool. I’ll feel free to—

SILVERMAN: Say pussy or whatever you want to. Why don’t we start talking about None of Us Ashes [the companion book to All of Us Flames] which could not come out at a better time. It’s just so beautiful and real and intense. Just that feeling, I would say as a godless but culturally Jewish person, I smell it in the air. I feel it in the wind. That none of us should be turned to ashes. I’ve interpreted a whole thing behind it.

FURMAN: Right on. In some ways it’s purposely vague. Insurgency as a stance that we’re going to have to keep. Something that we’re going to have to retain for the long haul. I was trying to make something about not wanting to burn out. At some point I got a phone, it went in my pocket, and terrible emergencies are delivered to it hourly. A lot of people went into a mode of extreme anxiety-rage, a helpful thing, but also how does that become sustainable? That’s what I think about. I was trying to write about taking those stances and making them last, and how to wait a long time to get what you want in terms of justice. I’m glad it makes sense. I’m glad you listened to it.

SILVERMAN: I mean, the words, “This city is the bearer of an old and secret curse / It’s not written in your bibles, it’s a verse behind the verse / Only visible to an obsessive detail-oriented heathen Jew / But it’s the hidden and unspoken that will thunder when the train comes through.” I was like, “Wow, God.”

FURMAN: The line between being a cultural Jew and a religious Jew actually gets more blurry.

SILVERMAN: This probably isn’t the direction you wanted to go. But what David Baddiel says, he has no religion. He’s just culturally Jewish but the Nazis would still break down his door. They don’t care if you follow the religion. It’s a crime of birth.

FURMAN: My grandmother told my dad the reason she sent him to Hebrew school when they went to America. She grew up in Germany and was a Holocaust refugee. And she was like, “I’m sending you to Hebrew school because when the government came to kill me for being Jewish, I didn’t even know what that was or what that was about. When they come to kill you, you’ll know more about it.” And that was her rationale for sending her to a religious school, which is really brutal.

SILVERMAN: Tell me about the album. The songs are so filmic. I can picture a music video to each one, or that it’s some narrative film under it.

FURMAN: I was worried that it was too serious. You get one record every three, four or five years. That causes there to be pressure. For me, I’m like, “Is it the last thing I ever make?” Or, “This is my thing that I have to play for years, and it’s got to be so important.”

SILVERMAN: That pressure can be paralyzing. Completely paralyzing. It’s why writers have such a hard time writing because you need to just be able to write the bad version just to start, to work off of something. Just to break the fear of it needing to be perfect.

FURMAN: And I don’t really get scared. I just push aside a bunch of other stuff that’s not as serious or write stupid things and funny things that maybe next time around I’ll do The White Album where you put everything in and it’s a giant pile.

SILVERMAN: It’s similar with comedy. Anything can be cohesive really. The brain hops from one thought to the next without segues. But there is something cohesive about this album. It’s that perfect album to put in your ears and walk through the streets and think of it as the soundtrack to your life. When you see an awesome spy thriller movie and you walk out of the theater and in your mind when you’re going to the bathroom, you’re like a spy for just a few minutes after you leave. You’re still in it.

FURMAN: It’s almost like the purpose of it. The thing I like about music so much is that it’s around you. It’s still in your head. It goes around with you and it’s in the air.

SILVERMAN: In the way that when you smell a person’s fart, their actual poop is inside you, the molecules or music gets inside you and it becomes a part of the listener. Is that beautiful?

FURMAN: [Laughs] That’s an analogy.

SILVERMAN: Wasn’t that worth interrupting? What you were probably going to say was something brilliant and I got like, “Wait, stop talking. I have a brilliant analogy about shit.” Sorry.

FURMAN: I feel like I’m being reviewed by Lester Bangs or something. No, that’s an iconic Sarah Silverman music review.

SILVERMAN: I meant it in the best possible way.

FURMAN: I take it well.

SILVERMAN: [Laughs]

FURMAN: I have occasional encounters with comedians and my childhood dream was to be a comedian. That’s what I thought was my future. And I think all the time about why it fell apart, why I turned away from comedy and leaned into music. I had a whole rapport with my dad about comedy. We would talk about comedy and talk about what makes things funny. And I did sketch comedy in college.

SILVERMAN: What was your college sketch group called?

FURMAN: It was called “Major Undecided.” Crappy name, and I was there when it was forming, but I had come a little bit too late and I wasn’t in the clique. I wanted to call it the Sketch Commodores. And I felt like I was good at it. I was very bad at performing. I’m not an actor, but I was a good writer of things. And I felt like I got hurt by it. I was socially maladjusted in a bunch of ways. I found myself usually doing more things alone. And comedy felt too social.

SILVERMAN: Well, you are funny and you’re a great performer and there is some connection between musicians and comedians. They both look over the fence, like “That could have been a path possibly taken.” We have a lot of respect for each other. I’ve opened for bands and music has been part of comedy shows. But you are funny.

FURMAN: It feels to me it comes from the same part of the brain, a song and a joke. You know what’s coming and you kind of don’t. And it’s very satisfying when it resolves in the way you wanted to, but also surprises you.

SILVERMAN: Looking for those not obvious, back-door connections to things.

FURMAN: Or setting up the audience’s attention. And then they’re like, “Is it going to land?” And then it does somehow. And the pleasure is in finding out how it lands. What made me start thinking about [comedy] more is being a parent of a little baby and seeing in particular what makes him laugh, I feel like it retaught me what humor is.

SILVERMAN: Because you’re seeing a completely unaffected soul, modified by nothing. Just what that soul finds funny. It’s pure.

FURMAN: And how a joke to a baby is just that he knows what’s coming, but he doesn’t know when. That’s the entirety of it. The barest version of a joke is what a joke for a baby is.

SILVERMAN: How old is he? Three? Two?

FURMAN: He’s not four yet. He will be pretty soon.

SILVERMAN: I’ve got a lot of material for four year olds.

FURMAN: You do?

SILVERMAN: Yeah.

FURMAN: What do you got?

SILVERMAN: They love this one. They love when you yell at them, you might go, “I’m taking a nap. Don’t wake me up.” And then you go “Zzzz…mi mi mi…Zzzz” and then they poke you and you go, “Who woke me up? Was it you?” Then they go, “No.” It’s a good one.

FURMAN: That’s a good one.

SILVERMAN: They have to know you’re kidding. There’s an age a little too early where they’re just upset. But when they know, they like it.

FURMAN: [Laughs] I started to think, especially in old fashioned songs and old country songs, something very similar is at play. They have a tagline and it’s coming.

SILVERMAN: I love it. It’s a choice. It gives you a limit to work within. And to me, limits are the foundation of art no matter how much we push against it. Even in television comedy, the dumbest network notes can force you to figure out something even better, because of those limits. That’s why the best art comes out of oppression. And I’m not saying that oppression is good, but its limits in art are the things that make a flower push through the cracks of pavement.

FURMAN: It makes you make a choice. It’s always better to make a strong choice.

SILVERMAN: I’ve been listening to the song “Peggy-O.” You know the song “Peggy-O?”

FURMAN: Vaguely, I can’t remember it.

SILVERMAN: It’s just so simple. It’s just so aggressively simple and it’s beautiful.

FURMAN: I think about this a lot. Romantic cliches sometimes seem like they can hold way more somehow. They can feel the constraint of those cliches or maybe the constraints of what you could say on the radio and it makes it all electric. All they want to say is that they want to have sex, but they can’t say that on the radio, so it becomes this grand opera.

SILVERMAN: It is interesting. It’s like with your music, too, it can be just a voice and a guitar but the way you produce, it sounds like big music.

FURMAN: It’s a lot of bells and whistles. Standup always scared the shit out of me. I don’t understand. You got nothing to lean on. It’s so stark, it’s so intense.

SILVERMAN: Any rejection comes immediately. It’s like performing for a focus group because they tell you immediately their temperature on every joke and beat.

FURMAN: This was my problem with comedy, maybe it’s not a comedian’s problem, but it’s hard to know how much to trust the audience.

SILVERMAN: Yes. Sometimes they don’t laugh and I know they’re wrong in my heart and sometimes they laugh too hard and I’m just like, “Well, they’re just really excited to be here.” You have to gauge it.

FURMAN: I’ve softened on this, but sometimes it fundamentally flattens things. I was afraid of the lowest common denominator motivation.

SILVERMAN: If that’s a fear you have, then you don’t want to do comedy. When I get in that rut, I’m not my best self. Because what you really want to do is expect the very best from the crowd and expect them to rise to the occasion. It’s a struggle. But you want to go in thinking that they’re your best friends instead of expecting the worst from them because it manifests. Adam Carolla asked me to do a set before he was headlining. And I said, “Yeah,” because I want to be in front of that crowd. I want to be in front of crowds that aren’t there necessarily for me and are in fact there for someone like him. They were great. I could have gone in expecting them to boo me or to be Trump people. Whoever they were, I decided that they were going to love me and I was going to love them. And I did. It was great. And then that same night I went and opened for Pussy Riot. I was very excited for that experiment. But I’m at a place where I want to be. I love when fans come out and see my show and they know me. But I also really like the challenge of getting outside of my own echo chamber as much as possible personally.

FURMAN: I feel like such a fraud when I get a big laugh on stage in between songs. I was thinking of myself as a funny person, and I just tell some weak ass joke. And it’s the funniest thing in the world. If an audience expecting comedy heard that same joke, it would be crickets.

SILVERMAN: I know what you’re saying. People say to me like, “Oh you’re such a good singer.” Because sometimes I sing in comedy and I’m like, “Thank you. I am a good singer for a comedian. You came expecting nothing from me in terms of that.” But if I were to present myself as a singer, it would be very, very different. But when musicians talk in between songs, it’s pretty awesome when you find out that they have a sense of humor.

FURMAN: Yeah, like a wedding toast. People just make the lightest little joke and kill.

SILVERMAN: Look, Clinton played the saxophone on Arsenio Hall and everyone was blown away. You wouldn’t find him getting a job as a saxophonist around town.

FURMAN: [Laughs] What are you working on?

SILVERMAN: I’m doing my podcast, which just came about because the world shut down and I had no way to do comedy or express myself. And then it became a very different podcast than I planned because it’s really the people that call in that create the trajectory of any episode. And it’s gotten very serious. I try to keep it light. I know musicians that play really happy music that are depressed souls. And then I know musicians that play heartbreaking folk tunes and they’re so happy and silly in life because that part of them is expressed.

FURMAN: You’re not carrying it around. With people who don’t make art, I’m like, “How are you getting through? I don’t understand what you’re doing with all that. Where does that go?”

SILVERMAN: There is a very common protection most people have around feeling too much. It’s also a burden.

FURMAN: I wonder if other people turn off emotions. In a way, what we do is a different way of domesticating emotions. I put them here in the work that I do and that’s where they are.

SILVERMAN: I do think a lot of people, including us, take trauma and put it away and it hurts to bring it up. Obviously if we do work through it, that’s a good thing. But who wants to do it? And we put it here and we just don’t go there. We’re paralyzed by wanting our work to be good enough and worthy that we don’t just sit down and put a pen in our hand. It should be as mindless as exercising. Just put your sneakers on and don’t think about it. It’s the same for writing. Literally every day I have a set at night, I spend my day going like, “Ugh, I don’t want to go. I don’t feel well.” The negotiating is insane. Just don’t think about it and show up and do it. Writing is that same way. Just put your hands on the keypad or put your pen in your hand. And I always just write the terrible version because then at least I’m working off of something.

FURMAN: I feel like the strongest thing, stronger than embarrassment or shame, has become like, “But who cares?” Even if I just write something and diligently finish it and I’m like, “I guess it’s good. Who cares that it’s good?” I’ve been interrogating this a lot lately. Is this a good thing or a bad thing that I have? The need to matter. I want to care about the things that I’m writing about and believe in them.

SILVERMAN: Think about the music and the musicians that influenced you, that brought you joy, that had deep meaning for you. And I wonder if the meaning for the musicians themselves is as deep as that. If they were so critical, if they didn’t want to put it out because they couldn’t foresee it being important enough, then they probably wouldn’t have any music. But listen, I get it.

FURMAN: We’re doing Zoom therapy right now. It’s good.

SILVERMAN: I understand everything you’re saying, and I need to hear it too.

FURMAN: I always keep in mind that it’s really not for me and I never really get to hear it or see what I’m making as other people see it. I’ll just never be able to hear it that way. I’m way too close to it. Sometimes, seven years go by and I hear something but I have become a different person. And then I’m like, “I can hear that.” I can hear what it sounds like to someone who didn’t toil over it. But it takes that long.

SILVERMAN: That’s really interesting, that perspective and time is what gives you grace towards your own work.

FURMAN: You have your time and your mic. That’s the beauty of it. Well, It’s nearly time for me to go feed my young child.

SILVERMAN: Good seeing you, my friend. I love your new album.

FURMAN: Thanks.

SILVERMAN: Hope to see you when you’re in LA. Peace out.